Education and Scientific Learning

Centers of Learning:

Keeping

in view the importance of knowledge highlighted by Qur’an and the Prophet

(peace be upon him), the system of education in the Muslim world was developed.

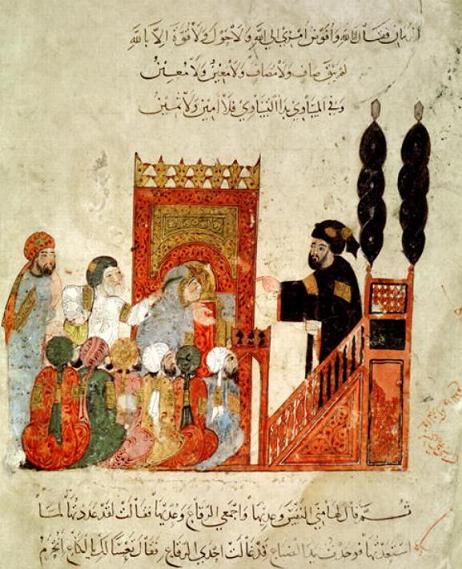

The learning took place in a variety of institutions, among them; the Maktab (kuttab),

or elementary school; the palace schools; the Halqah, or study circle,

bookshops and literary salons; and the various types of colleges, the meshed,

the Masjid, and the madrasah. All the schools taught essentially

the same subjects. The simplest type of early Muslim education was offered in

the mosques, where scholars who had congregated to teach the Qur’an and Hadith

began, before long, to teach the religious sciences to the keen adults.

Mosques

increased in number under the caliphs, Some mosques, such as that of al-Mansur,

built during the reign of Harun ar-Rashid in Baghdad, or those in Isfahan,

Mashhad, Ghom, Damascus, Cairo, and the Alhambra (Granada-Spain), became

centres of learning for students from all over the Muslim world. Each mosque

usually contained several study circles (Halqah), so named because the teacher

was, as a rule, seated on a dais or cushion with the pupils gathered in a

semicircle before him.

Elementary

schools (maktab, or kuttab), in which pupils learned to read and

write, were developed into centres for instruction in elementary Islamic

subjects. Students were expected to memorize the Qur’an as perfectly as

possible. Some schools also included in their curriculum the study of poetry,

elementary arithmetic, physical sciences, penmanship, ethics (manners), and

elementary grammar. Maktabs were quite common in almost every town or village

in the Middle East, Asia,

Africa, Sicily,

and Spain.

Institutions

and Universities:

Madrasahs

existed as early as the 9th century, but the most famous one was founded in

1057 by the vizier Nizam al-Mulk in Baghdad.

The Nizamiyah, devoted to Sunnite learning, served as a model for the establishment

of an extensive network of such institutions throughout the eastern Islamic

world, especially in Cairo, which had 75 madrasahs, in Damascus, which had 51,

and in Aleppo, where the number of madrasahs rose from six to 44 between 1155

and 1260. Important institutions also developed in the Spanish cities of Cordoba, Seville, Toledo, Granada,

Murcia, Almería, Valencia,

and Cádiz, in western Islam, under the Umayyads.

Al-Azhar University at Cairo, Egypt

is the chief centre of Islamic and Arabic learning in the world, founded by the

Fatimids in 970 C.E with a large public liberary and several colleges. The

basic program of studies was, and still is, Islamic law, theology, and the

Arabic language.

Later

the philosophy, medicine and sciences were added to the curriculum. Gradually

these subjects got eliminated after having reached climax resulting in decline.

In the 19th century philosophy was reinstated. The modernization have resulted

in the addition of social sciences at its new supplementary campus. Presently a

number of Islamic Universities have been established in the Muslim countries

where apart from theology, the other sciences are also taught, but they are few

in numbers. There are thousands of traditional madrasah and Dar-ul-Aloom in

countries with Muslim populations where only Islamic theology and religious

sciences are taught, producing millions of ulema (religious scholars) with

almost no knowledge of social, physical sciences and other branches of

knowledge.

Early Muslim Education:

Early

Muslim education emphasized practical studies, such as the application of

technological expertise to the development of irrigation systems, architectural

innovations, textiles, iron and steel products, earthenware, and leather

products; the manufacture of paper and gunpowder; the advancement of commerce;

and the maintenance of a merchant marine. After the 11th century, however,

denominational interests dominated higher learning, and the Islamic sciences

achieved preeminence. Greek knowledge was studied in private, if at all, and

the literary arts diminished in significance as educational policies

encouraging academic freedom and new learning were replaced by a closed system

characterized by an intolerance toward scientific innovations, secular

subjects, and creative scholarship. This denominational system spread

throughout eastern Islam between about 1050 and 1250 C.E.

Pursuit

of Scientific Knowledge & Libraries:

Thus

during first half of millennia of its history, Islamic civilization has been

keen to gain knowledge, be it physics, chemistry (alchemi), algebra,

mathematics, astronomy, medicine, social sciences, philosophy or any other

field. The high degree of learning and scholarship in Islam, particularly

during the 'Abbasid period in the East and the later Umayyads in West (Spain),

encouraged the development of bookshops, copyists, and book dealers in large,

important Islamic cities such as Damascus,

Baghdad, and Cordoba. Scholars and

students spent many hours in these bookshop schools browsing, examining, and

studying available books or purchasing favourite selections for their private

libraries. Book dealers traveled to famous bookstores in search of rare

manuscripts for purchase and resale to collectors and scholars and thus

contributed to the spread of learning. Many such manuscripts found their way to

private libraries of famous Muslim scholars such as Avicenna, al-Ghazali, and

al-Farabi, who in turn made their homes centres of scholarly pursuits for their

favourite students.

Islam in Renaissance

& Enlightenment:

Europe owes it awakening form the dark ages to

the Renaissance and Enlightenment by the transfer of knowledge including lost

Greek heritage through the Muslim scholars and centers of learning at Spain and their

contact with the Muslim world through Crusades. As long as Muslims continued

the pursuit of all branches of useful worldly knowledge of physical science,

technology along with the religious sciences, the Islamic Civilization was at

its zenith.

Stages of

Evolution of Learning Process:

The education

and learning process may be divided in to various stages among the Muslims. The

renaissance of Islamic culture and scholarship developed largely under the

'Abbasid administration in Eastern side and under the later Umayyads in the

West, mainly in Spain,

between 800 and 1000 C.E. This latter stage, the golden age of Islamic

scholarship, was largely a period of translation and interpretation of

classical thoughts and their adaptation to Islamic theology and philosophy. The

period also witnessed the introduction and assimilation of Hellenistic,

Persian, and Indian knowledge of mathematics, astronomy, algebra, trigonometry,

and medicine into Muslim culture. Whereas the 8th and 9th centuries, mainly

between 750 and 900 C.E, were characterized by the introduction of classical

learning and its refinement and adaptation to Islamic culture, the 10th and

11th were centuries of interpretation, criticism, and further adaptation. There

followed a stage of modification and significant additions to classical culture

through Muslim scholarship. Then, during the 12th and 13th centuries, most of

the works of classical learning and the creative Muslim additions were

translated from Arabic into Hebrew and Latin. The creative scholarship in Islam

from the 10th to the 12th century included works by such scholars as Omar

Khayyam, al-Biruni, Fakhr ad-Din ar-Razi, Avicenna (Ibn Sina), at-Tabari,

Avempace (Ibn Bajjah), and Averroës (Ibn Rushd).

Muslim

Contributions in Medicine, Science & Technology:

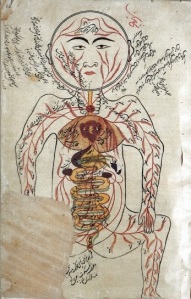

The

contributions in the advancement of knowledge by the traditional Islamic

institutions of learning (Madrasahs, Maktab, Halqa & Dar-ul-Aloom) are

enormous, which have been summed up in Encyclopedia Britannica: “The madrasahs generally offered instruction

in both the religious sciences and other branches of knowledge. The

contribution of these institutions to the advancement of knowledge was vast.

Muslim

scholars calculated the angle of the ecliptic; measured the size of the Earth;

calculated the precession of the equinoxes; explained, in the field of optics

and physics, such phenomena as refraction of light, gravity, capillary

attraction, and twilight; and developed observatories for the empirical study

of heavenly bodies. They made advances in the uses of drugs, herbs, and foods for

medication; established hospitals with a system of interns and externs;

discovered causes of certain diseases and developed correct diagnoses of them;

proposed new concepts of hygiene; made use of anesthetics in surgery with newly

innovated surgical tools; and introduced the science of dissection in anatomy.

Muslims

furthered the scientific breeding of horses and cattle; found new ways of

grafting to produce new types of flowers and fruits; introduced new concepts of

irrigation, fertilization, and soil cultivation; and improved upon the science

of navigation. In the area of chemistry, Muslim scholarship led to the

discovery of such substances as potash, alcohol, nitrate of silver, nitric

acid, sulfuric acid, and mercury chloride.

Muslims

scientists also developed to a high degree of perfection the arts of textiles,

ceramics, and metallurgy.” According to a US study published by the American

Association for the Advancement of Science in its Journal on 21 February

2007; ‘Designs on surface tiles in the

Islamic world during the Middle Ages revealed their maker’s understanding of

mathematical concepts not grasped in the West until 500 years later. Many

Medieval Islamic buildings walls have ornate geometric star and polygon or

‘girih’, patterns, which are often overlaid with a swirling network of lines -

This girih tile method was more efficient and precise than the previous

approach, allowing for an important breakthrough in Islamic mathematics and

design.’

Muslims

Scholars of Theology and Science:

According

to the famous scientist Albert Einstein; “Science without religion is lame.

Religion without science is blind.” Francis Bacon, the famous philosopher, has

rightly said that a little knowledge of science makes you an atheist, but an

in-depth study of science makes you a believer in God. A critical analysis

reveals that most of Muslim scientists and scholars of medieval period were

also eminent scholars of Islam and theology. The earlier Muslim scientific

investigations were based on the inherent link between the physical and the

spiritual spheres, but they were informed by a process of careful observation

and reflection that investigated the physical universe.

Influence

of Qur’an on Muslims Scientists:

The

worldview of the Muslims scientists was inspired by the Qur’an and they knew

that: “Surely, In the creation of the heavens and the earth; in the alternation

of the night and the day, in the sailing of the ships through the ocean for the

profit of mankind; in the rain which Allah sends down from the skies, with

which He revives the earth after its death and spreads in it all kinds of

animals, in the change of the winds and the clouds between the sky and the

earth that are made subservient, there are signs for rational

people.”(Qur’an;2:164). “Indeed in the alternation of the night and the day and

what Allah has created in the heavens and the earth, there are signs for those

who are God fearing.”(Qur’an;10:6). They were aware that there was much more to

be discovered. They did not have the precise details of the solar and lunar

orbits but they knew that there was something extremely meaningful behind the

alternation of the day and the night and in the precise moveme

nts of the sun

and the moon as mentioned in Qur’an: One can still verify that those who

designed the dome and the minaret, knew how to transform space and silence into

a chanting remembrance that renews the nexus between God and those who respond

to His urgent invitation.

Famous Muslim

Scientists and Scholars:

The

traditional Islamic institutions of learning produced numerous great

theologians, philosophers, scholars and scientists. Their contributions in

various fields of knowledge indicate the level of scholarship base developed

among he Muslims one thousand years ago. Only few are being mentioned here:

Chemistry:

Jabir

ibn Hayyan, Abu Musa (721-815), alchemist known as the "father of

chemistry." He studied most branches of learning, including medicine. After

the 'Abbasids defeated the Umayyads, Jabir became a court physician to the

'Abbasid caliph Harun ar-Rashid. Jabir was a close friend of the sixth Shi'ite

imam, Ja'far ibn Muhammad, whom he gave credit for many of his scientific

ideas.

Mathematics,

Algebra, Astronomy & Geography:

Al-Khwarizmi

(Algorizm) (770–840 C.E) was a researcher of mathematics, algorithm, algebra,

calculus, astronomy & geography. He compiled astronomical tables,

introduced Indian numerals (which became Arabic numerals), formulated the

oldest known trigonometric tables, and prepared a geographic encyclopedia in

cooperation with 69 other scholars.

Physics,

Philosophy, Medicine:

Ibn Ishaq

Al-Kindi (Alkindus) (800–873 C.E) was an intellectual of

philosophy, physics, optics, medicine, mathematics & metallurgy.

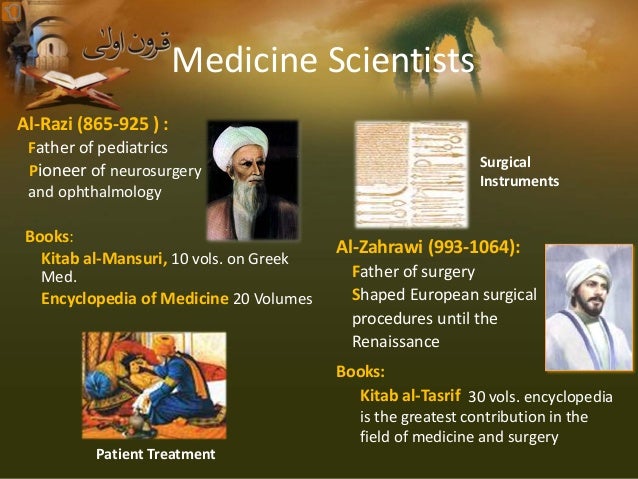

Ali Ibn

Rabban Al-Tabari(838–870 C.E) was a scholar in medicine, mathematics,

calligraphy & literature. Al-Razi (Rhazes) (864– 930 C.E), a physical and

scientist of medicine, ophthalmology, smallpox, chemistry & astronomy.

Ar-Razi's two

most significant medical works are the Kitab al-Mansuri, which became well

known in the West in Gerard of Cremona's 12th-century Latin translation; and

‘Kitab al-hawi’, the "Comprehensive Book".

Among

his numerous minor medical treatises is the famed Treatise on the Small Pox and

Measles, which was translated into Latin, Byzantine Greek, and various modern

languages.

Al-Farabi

(Al-Pharabius) (870- 950 C.E) excelled in sociology, logic, philosophy, political

science & music. Abu Al-Qasim Al-Zahravi (Albucasis; 936 -1013 C.E) was an

expert in surgery & medicine known as the father of modern surgery.

Ibn

Al-Haitham (Alhazen) (965-1040 C.E); was the mathematician and

physicist who made the first significant contributions to optical theory since

the time of Ptolemy (flourished 2nd century).

In his

treatise on optics, translated into Latin in 1270 as Opticae thesaurus Alhazeni

libri vii, Alhazen published theories on refraction, reflection, binocular

vision, focusing with lenses, the rainbow, parabolic and spherical mirrors,

spherical aberration, atmospheric refraction, and the apparent increase in size

of planetary bodies near the Earth's horizon. He was first to give an accurate

account of vision, correctly stating that light comes from the object seen to

the eye.

Abu

Raihan Al-Biruni (973-1048 C.E);

was a

Persian scholar and scientist, one of the most learned men of his age and an

outstanding intellectual figure. Al-Biruni's most famous works are Athar

al-baqiyah (Chronology of Ancient Nations); at-Tafhim ("Elements of

Astrology"); al-Qanun al-Mas'udi ("The Mas'udi Canon"), a major

work on astronomy, which he dedicated to Sultan Mas'ud of Ghazna; Ta'rikh

al-Hind ("A History of India"); and Kitab as-Saydalah, a treatise on

drugs used in medicine.

In his works on astronomy, he discussed with approval

the theory of the Earth's rotation on its axis and made accurate calculations

of latitude and longitude. He was the first one to determine the

circumference earth. In the filed of physics, he explained natural springs

by the laws of hydrostatics and determined with remarkable accuracy the

specific weight of 18 precious stones and metals. In his works on geography, he

advanced the daring view that the valley of the Indus

had once been a sea basin.

Ibn

Sina (Avicenna, 981–1037 C.E); was a scientist of medicine,

philosophy, mathematics & astronomy.

He was

particularly noted for his contributions in the fields of Aristotelian philosophy

and medicine. He composed the Kitab ash-shifa` ("Book of Healing"), a

vast philosophical and scientific encyclopedia, and the Canon of Medicine,

which is among the most famous books in the history of medicine.

Ibn

Hazm, (994-1064 C.E) was a Muslim litterateur, historian,

jurist, and theologian of Islamic Spain. One of the leading exponents of the

Zahiri (literalist) school of jurisprudence, he produced some 400 works,

covering jurisprudence, logic, history, ethics, comparative religion, and theology,

and The Ring of the Dove, on the art of love.

Al-Zarqali

(Arzachel) (1028-1087 C.E); an astronomer who invented astrolabe (an instrument

used to make astronomical measurements). Al-Ghazali (Algazel) (1058-1111 C.E);

was a scholar of sociology, theology & philosophy.

Ibn

Zuhr (Avenzoar) (1091-1161 C.E); was a scientist and expert

in surgery & medicine.

Ibn

Rushd (Averroes) (1128- 1198 C.E); excelled in philosophy,

law, medicine, astronomy & theology.

Nasir

Al-Din Al-Tusi (1201-1274 C.E); was the scholar of astronomy and

Non-Euclidean geometry.

Geber

(flourished in 14th century Spain)

is author of several books that were among the most influential works on

alchemy and metallurgy during the 14th and 15th centuries. A number of Arabic

scientific works credited to Jabir were translated into Latin during the 11th

to 13th centuries. Thus, when an author who was probably a practicing Spanish

alchemist began to write in about 1310. Four works by Geber are known: Summa

perfectionis magisterii (The Sum of Perfection or the Perfect Magistery, 1678),

Liber fornacum (Book of Furnaces, 1678), De investigatione perfectionis (The

Investigation of Perfection, 1678), and De inventione veritatis (The Invention

of Verity, 1678).

They

are the clearest expression of alchemical theory and the most important set of

laboratory directions to appear before the 16th century. Accordingly, they were

widely read and extremely influential in a field where mysticism, secrecy, and

obscurity were the usual rule. Geber's rational approach, however, did much to

give alchemy a firm and respectable position in Europe.

His practical directions for laboratory procedures were so clear that it is

obvious he was familiar with many chemical operations. He described the

purification of chemical compounds, the preparation of acids (such as nitric

and sulfuric), and the construction and use of laboratory apparatus, especially

furnaces. Geber's works on chemistry were not equaled in their field until the

16th century with the appearance of the writings of the Italian chemist

Vannoccio Biringuccio, the German mineralogist Georgius Agricola, and the

German alchemist Lazarus Ercker.

Muhammad

Ibn Abdullah (Ibn Battuta) (1304-1369 C.E); was a world traveler, he

traveled 75,000 mile voyage from Morocco to China and back.

Ibn Khaldun(1332-1395 C.E) was an expert on sociology, philosophy of history

and political science.

Tipu,

Sultan of Mysore

(1783-1799 C.E) in the south of India,

was the innovator of the world's first war rocket. Two of his rockets, captured

by the British at Srirangapatana, are displayed in the Woolwich Museum of

Artillery in London.

The rocket motor casing was made of steel with multiple nozzles. The rocket,

50mm in diameter and 250mm long, had a range performance of 900 meters to 1.5

km.

Turkish

scientist Hazarfen Ahmet Celebi took off from Galata tower and flew over the

Bosphorus, two hundred years before a comparable development elsewhere. Fifty years later Logari Hasan Celebi,

another member of the Celebi family, sent the first manned rocket into upper

atmosphere, using 150 okka (about 300 pounds) of gunpowder as the firing fuel.

Contribution

of Great Muslim Women & Scholars:

Islam

does not restrict acquisition of knowledge to men only, the women are equally

required to gain knowledge. Hence many eminent women have contributed in

different fields. Aishah as-Siddiqah (the one who affirms the Truth), the

favourite wife of Propeht Muhammad (peace be upon him), is regarded as the best

woman in Islam. Her life also substantiates that a woman can be a scholar,

exert influence over men and women and provide them with inspiration and

leadership. Her life is also an evidence of the fact that the same woman can be

totally feminine and be a source of pleasure, joy and comfort to her husband.

The example of Aishah in promoting education and in particular the education of

Muslim women in the laws and teachings of Islam is one which needs to be

followed. She is source of numerous Hadith and has been teaching eminent

scholars. Because of the strength of her personality, she was a leader in every

field in knowledge, in society and in politics.

Sukayna (also

“Sakina), the great granddaughter of the Prophet (peace be upon him), and

daughter of Imam Husain was the most brilliant most accomplished and virtuous

women of her time. She grew up to be an outspoken critic of the Umayyads. She

became a political activist, speaking against all kinds of tyranny and

personal, social and political iniquities and injustice. She was a fiercely

independent woman. She married more than once, and each time she stipulated

assurance of her personal autonomy, and the condition of monogamy on the

prospective husband’s part, in the marriage contract. She went about her

business freely, attended and addressed meetings, received men of letters,

thinkers, and other notables at her home, and debated issues with them. She was

an exceedingly well-educated woman who would take no nonsense from anyone

howsoever high and mighty he or she might be.

Um

Adhah al-Adawiyyah (d. 83 AH), reputable scholar and narrator of Hadith

based on reports of Ali ibn Abu Talib and Ayesha; Amrah bint Abd al-Rahman (d.

98 AH), one of the more prominent students of Ayesha and a known legal scholar

in Madina whose opinions overrode those of other jurists of the time; Hafsa

bint Sirin al-Ansariyyah (d. approx. 100 AH), also a legal scholar. Amah

al-Wahid (d. 377 AH), noted jurist of the Shafaii school and a mufti in Baghdad; Karimah bint

Ahmad al-Marwaziyyah (d. 463 AH), teacher of hadith (Sahih Bukhari); Zainab bint

Abd al-Rahman (d. 615 AH), linguist and teacher of languages in Khorasan.

Zainab bint Makki (d. 688 AH) was a prominent scholar in Damascus, teacher of

Ibn Taimiya, the famous jurist of the Hanbali school; Zaynab bint Umar bin

Kindi (d. 699 AH), teacher of the famous hadith scholar, al-Mizzi; Fatima bint

Abbas (d. 714 AH), legal scholar of the Hanbali school, mufti in Damascus and

later in Cairo; Nafisin bint al Hasan taught hadith; Imam Shafaii sat in her

teaching circle at the height of his fame in Egypt. Two Muslim women — Umm Isa

bint Ibrahim and Amat al-Wahid — served as muftis in Baghdad. Ayesha al-Banniyyah, a legal scholar

in Damascus,

wrote several books on Islamic law. Umm al-Banin (d. 848 AH/ 1427 CE) served as

a mufti in Morocco.

Al Aliyya was a famous teacher whose classes men attended before the noon prayer (Zuhr) and women after

the afternoon prayer (Asr). A Muslim woman of the name of Rusa wrote a textbook

on medicine, and another, Ujliyyah bint al-Ijli (d. 944 CE) made instruments to

be used by astronomers. During the Mamluk period in Cairo (11th century) women established five

universities and 12 schools which women managed.

Rabi’a

al-Adawiyya al-Basri (717 C.E), is honored as one of the earliest and greatest

sufis in Islam. Orphaned as a child, she was captured and sold into slavery.

But later her master let her go. She retreated into the desert and gave herself

to a life of worship and contemplation. She did not marry, and to a man who

wanted her hand she said: “I have become naught to self and exist only through

Him. I belong wholly to Him. You must ask my hand of Him, not of me.” She

preached unselfish love of God, meaning that one must love Him for His own sake

and not out of fear or hope of rewards. She had many disciples, both men and women.

Zubaida

(Amatal Aziz bint Jafar), the favourite wife of

Harun al-Rashid, the legendary Abassid caliph. She came to be an

exceedingly wealthy woman, a billionaire so to speak, independently of her

husband. Granddaughter of Al-Mansur, she grew up to be a lady of dazzling

beauty, articulate and charming of speech, and great courage. Discerning and

sharp, her wisdom and insightfulness inspired immediate admiration and respect.

In her middle years she moved out of the royal “harem” and began living in a huge

palace of her own. She owned properties all over the empire which dozens of

agents in her employ managed for her. A cultivated woman, pious and well

acquainted with the scriptures, Zubaida was also a poetess and a patron of the

arts and sciences. She allocated funds to invite hundreds of men of letters,

scientists, and thinkers from all over the empire to locate and work in Baghdad. She spent much

of her funds for public purposes, built roads and bridges, including a 900-mile

stretch from Kufa to Makkah, and set up, hostels, eating places, and repair

shops along the way, all of which facilitated travel and encouraged enterprise.

She built canals for both irrigation and water supply to the people. She spent

many millions of Dinars on getting a canal built, that went through miles of

tunnel through mountains, to increase the water supply in Makkah for the

benefit of pilgrimages. She took a keen interest in the empire’s politics and

administration. The caliph himself sought her counsel concerning the affairs of

state on many occasions and found her advice to be eminently sound and

sensible. After Harun’s death, his successor, Al Mamun, also sought her advice

from time to time. She died in 841 C.E (32 years after Harun’s death).

Arwa

bint Ahmad bin Mohammad al-Sulayhi (born 1048 C.E) was the ruling

queen of Yemen for 70 years (1067-1138 C.E), briefly, and that only

technically, as a co-ruler with her two husbands, but as the sole ruler for

most of that time. She is still remembered with a great deal of affection in Yemen as a

marvellous queen. Her name was mentioned in the Friday sermons right after that

of the Fatimid caliph in Cairo.

She built mosques and schools throughout her realm, improved roads, took

interest in agriculture and encouraged her country’s economic growth. Arwa is

said to have been an extremely beautiful woman, learned, and cultured. She had

a great memory for poems, stories, and accounts of historical events. She had

good knowledge of the Qur’an and Sunnah. She was brave, highly intelligent,

devout, with a mind of her own. She was a Shi’a of the Ismaili persuasion, sent

preachers to India,

who founded an Ismaili community in Gujarat

which still thrives. She was also a competent military strategist. At one point

(1119 C.E) the Fatimid caliph sent a general, Najib ad-Dowla, to take over Yemen.

Supported by the emirs and her people, she fought back and forced him to go

back to Egypt.

She died in 1138 C.E at the age of 90. A university in Sana’a is named after

her, and her mausoleum in Jibla continues to be a place of pilgrimage for

Yemenis and others. The other eminent ladies who played important role in the

affairs of state and philanthropy include, Buran the wife of Caliph Mamun.

Among the Mughals Noor Jehan, Zaib un Nisa left their mark in Indian history.

Razia Sultan was an other eminent women ruler in India.

Influence

of Islamic Learning in Reviving Western Civilization:

While

Muslims were excelling in the field of knowledge and learning of science and

technology, the conditions of Christendom at this period was deplorable. Under Constantine and his

orthodox successors the Aesclepions were closed for ever, the public libraries

established by liberality of the pagan emperors were dispersed or destroyed.

Learning was branded as magic and punished as treason, philosophy and science

were exterminated. The ecclesiastical hatred against human learning had found

expression in the patristic maxims; “Ignorance is the mother of devotion” and

Pope Gregory the Great the founder of the doctrine of ‘supremacy of religious

authority’; gave effect to this obscurantist dogma by expelling from Rome all

scientific studies and burning the Palatine Library founded by Augustus Caesar.

He forbade the study of ancient writers of Greece and Rome. He introduced and sanctified the

mythological Christianity which continued for centuries as the predominating

creed of Europe with its worship of relics and

the remains of saints. Science and literature were placed under the ban by

orthodox Christianity and they succeeded in emancipating themselves only when

Free Thought had broken down the barriers raised by orthodoxy against the

progress of the human mind.

Phenomenal

influence of Islamic learning on the West:

The influence

of Islamic learning on the West has been phenomenal; an extract from

Encyclopedia Britannica is an eye opener for the Muslims:

“The decline of Muslim scholarship

coincided with the early phases of the European intellectual awakening that

these translations were partly instrumental in bringing about. The translation into Latin of most Islamic

works during the 12th and 13th centuries had a great impact upon the European

Renaissance. As Islam was declining in scholarship and Europe

was absorbing the fruits of Islam's centuries of creative productivity, signs

of Latin Christian awakening were evident throughout the European continent.

The 12th century was one of intensified traffic of Muslim learning into the

Western world through many hundreds of translations of Muslim works, which

helped Europe seize the initiative from Islam

when political conditions in Islam brought about a decline in Muslim

scholarship. By 1300 C.E when all that was worthwhile in Muslim scientific,

philosophical, and social learning had been transmitted to European schoolmen

through Latin translations, European scholars stood once again on the solid

ground of Hellenistic thought, enriched or modified through Muslim and

Byzantine efforts.”

“Most of the important Greek scientific

texts were preserved in Arabic translations. Although the Muslims did not alter

the foundations of Greek science, they made several important contributions

within its general framework. When interest in Greek learning revived in

western Europe during the 12th and 13th centuries, scholars turned to Islamic

Spain for the scientific texts. A spate of translations resulted in the revival

of Greek science in the West and coincided with the rise of the universities.

Working within a predominantly Greek framework, scientists of the late Middle

Ages reached high levels of sophistication and prepared the ground for the

scientific revolution of the 16th and 17th centuries.” According to Will

Durant, the Western scholar, “For five centuries , from 700 to 1200 (C.E),

Islam led the world in power, order and extent of government, in refinement of

manners, scholarship and philosophy”.

Related: